The Anatomy of a knife

There’s more to a custom knife than meets the eye…

Here you will learn about all the different terminology and design aspects of a knife. In this section I will cover:

- The Body of a knife

- Tang types: Hidden and Full

- Handles: Hidden Tang and Full Tang

- Bolsters: Hidden Tang and Full Tang

- Pommels: Hidden Tang; exposed and enclosed, and Full Tang

- Pins: Standard and Mosaic

- Blade types

- Bevels: Flat, Concave, and Convex

- Edges: Angle and Style

- Spine: Jimping, Swedges, and more

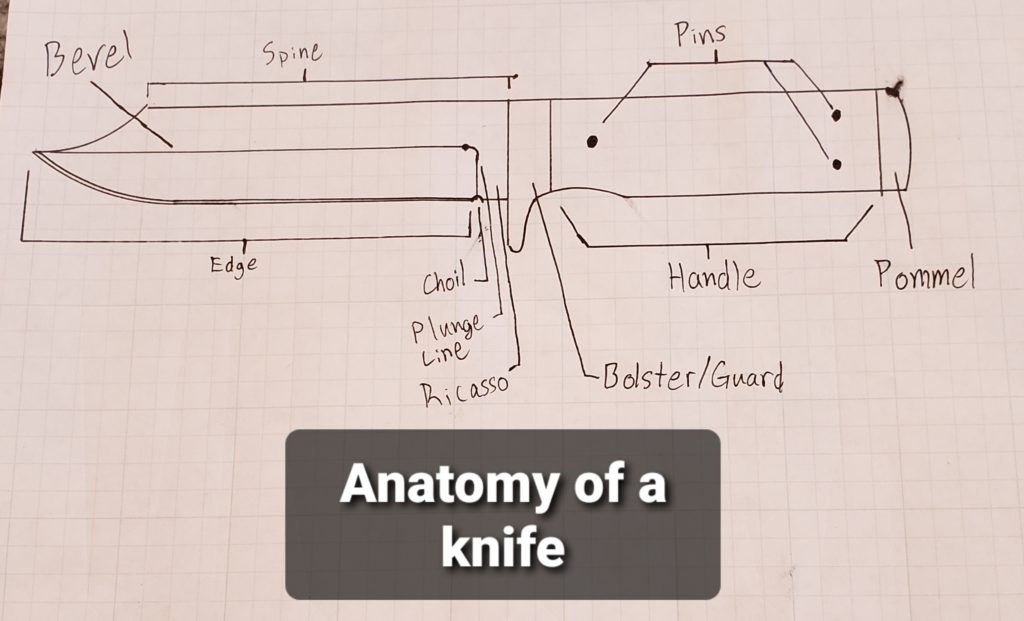

The Body of a Knife

- Bevel: thinned portion of the blade face, between the flat and the edge.

- Spine: exposed portion of metal on a blade, opposite the edge.

- Edge: sharpened portion of a knife. The cutting edge.

- Choil: an indented portion of the blade, behind the edge. This is used to demarcate the end of the edge.

- Plunge line: vertical line connecting the bevel line to the edge or choil.

- Ricasso: unsharpened portion of the blade located behind the edge and/or choil.

- Bolster/Guard: protective piece, usually made of metal, which prevents the fingers from sliding up the handle and onto the blade.

- Handle: the handle of the knife.

- Pins: circular rods, usually made of metal, that run through the cross section of the handle and tang, that aid in securing the handle to the tang.

- Pommel: solid piece of material at the end of the handle, usually made of metal.

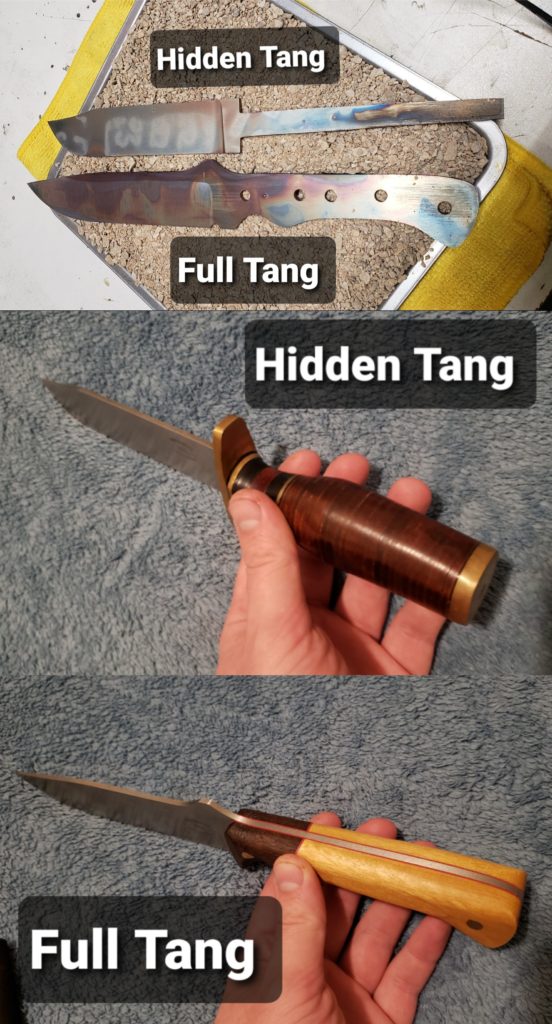

Tang types: Hidden and Full

The tang of a knife is the metal portion of the knife handle. The blade and tang are all one solid piece of metal.

Hidden Tang knives are aesthetically pleasing, but weaker by nature.

{*Note* Many makers will use a “partial” tang on their Hidden Tang knives, which only runs part of the length of the handle. I make all my hidden tang knives with tangs that run the full length of the handle for maximum possible durability. The only exception to this would be if the handle material used prevents the use of a full length tang. Some odd shaped natural materials (like certain pieces of antler) fall into this category. If your knife is made this way it will be noted on the Certificate of Authenticity as having a “partial length tang”.}

Full Tang knives are much stronger and better suited for hard use tasks.

Full Tang knives can be true full tang, or skeletonized.

- True Full Tang knives are completely solid all the way through, with the exception of pin holes.

- Skeleton Tang knives have additional holes drilled for weight reduction. This also helps the epoxy bond the handle scales to the tang more securely.

Handles: Hidden Tang and Full Tang

Bolsters: Hidden Tang and Full Tang

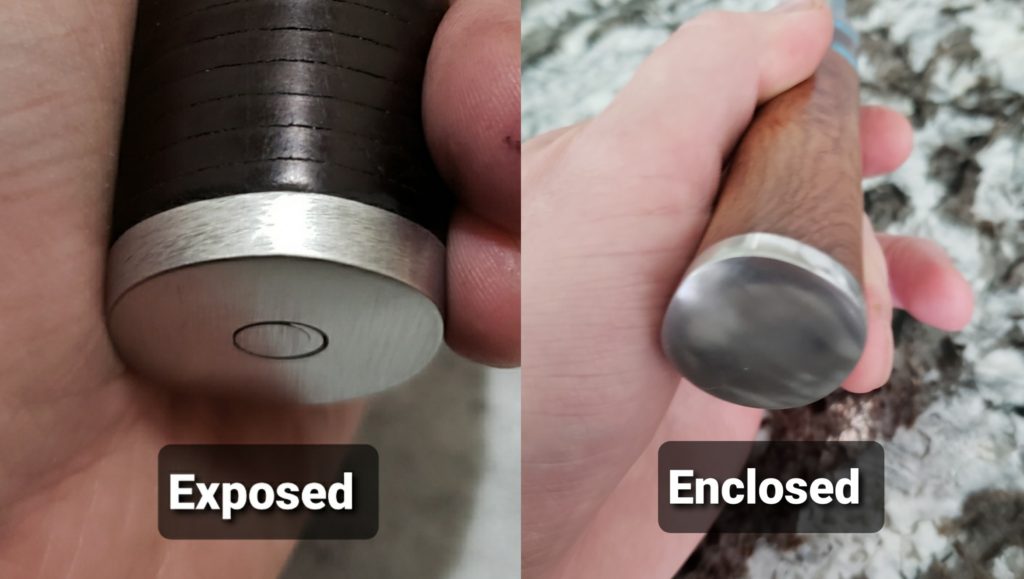

Pommels: Hidden Tang; exposed and enclosed, and Full Tang

Hidden Tang knives have the option of being exposed or enclosed at the pommel.

Exposed tangs have a pommel which has been drilled and tapped with threads. The pommel is then screwed onto the threaded end of the tang. The end of the tang is visible in the center of the pommel.

Enclosed tangs are secured to the pommel inside of the handle. This can be accomplished in a variety of different ways, depending on the knife in question. The tang is NOT visible this way. This gives a much cleaner, more polished appearance, but is more time consuming and costly.

Full Tang knives generally only use one type of pommel: two slabs of material on either side of the tang, secured by pins, epoxy, or other means.

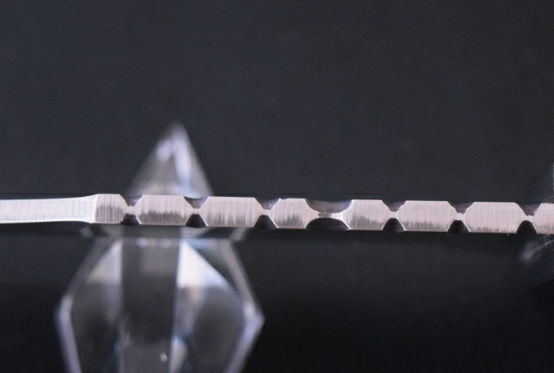

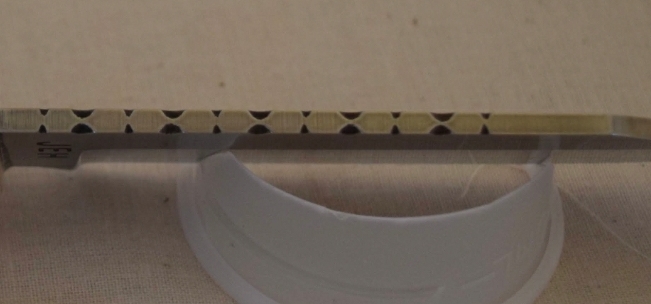

Pins: Standard and Mosaic

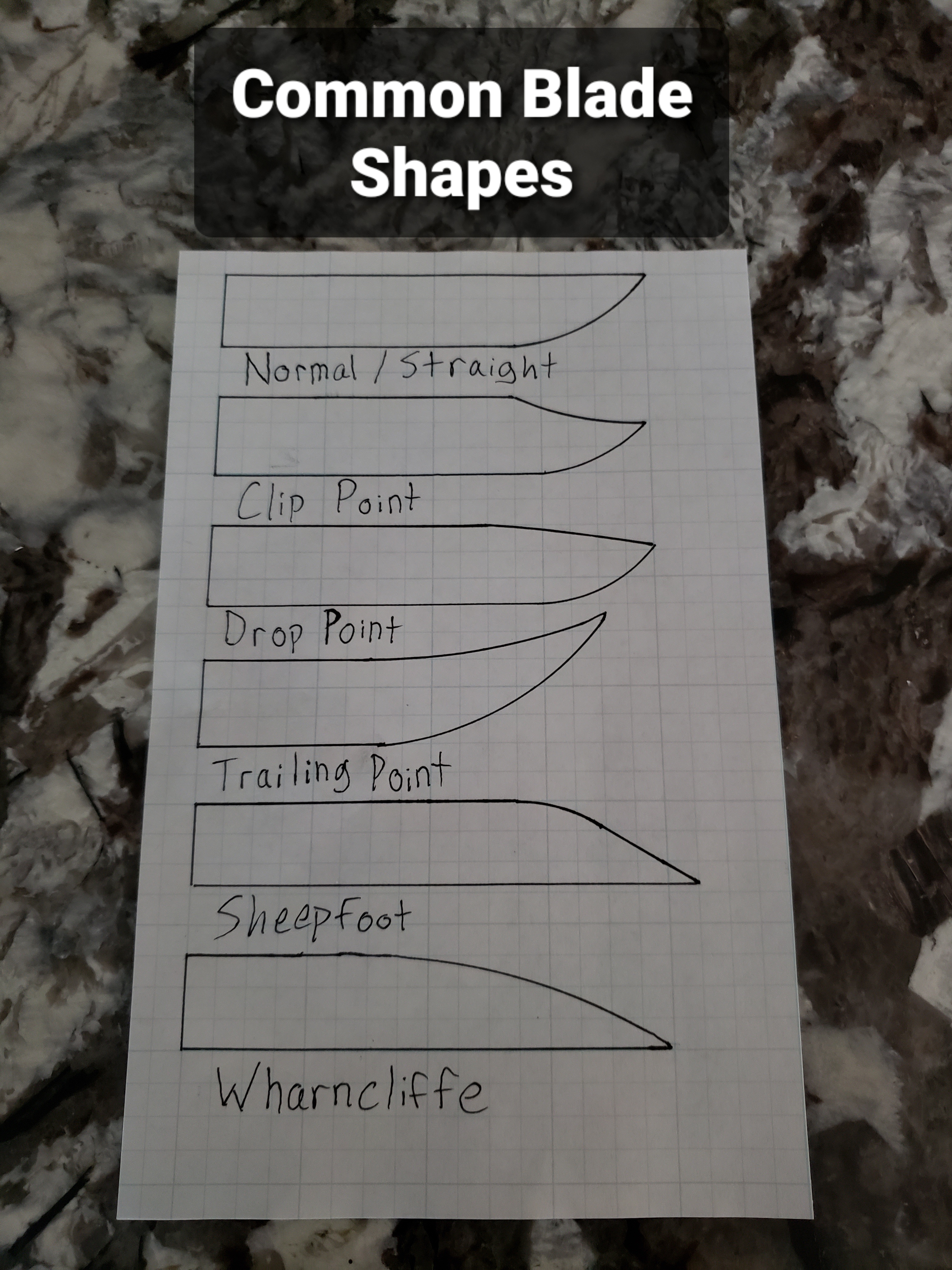

Blade Types

There are dozens of different blade types to choose from. These are some of the most popular.

Blade Bevels: Flat, Concave, and Convex

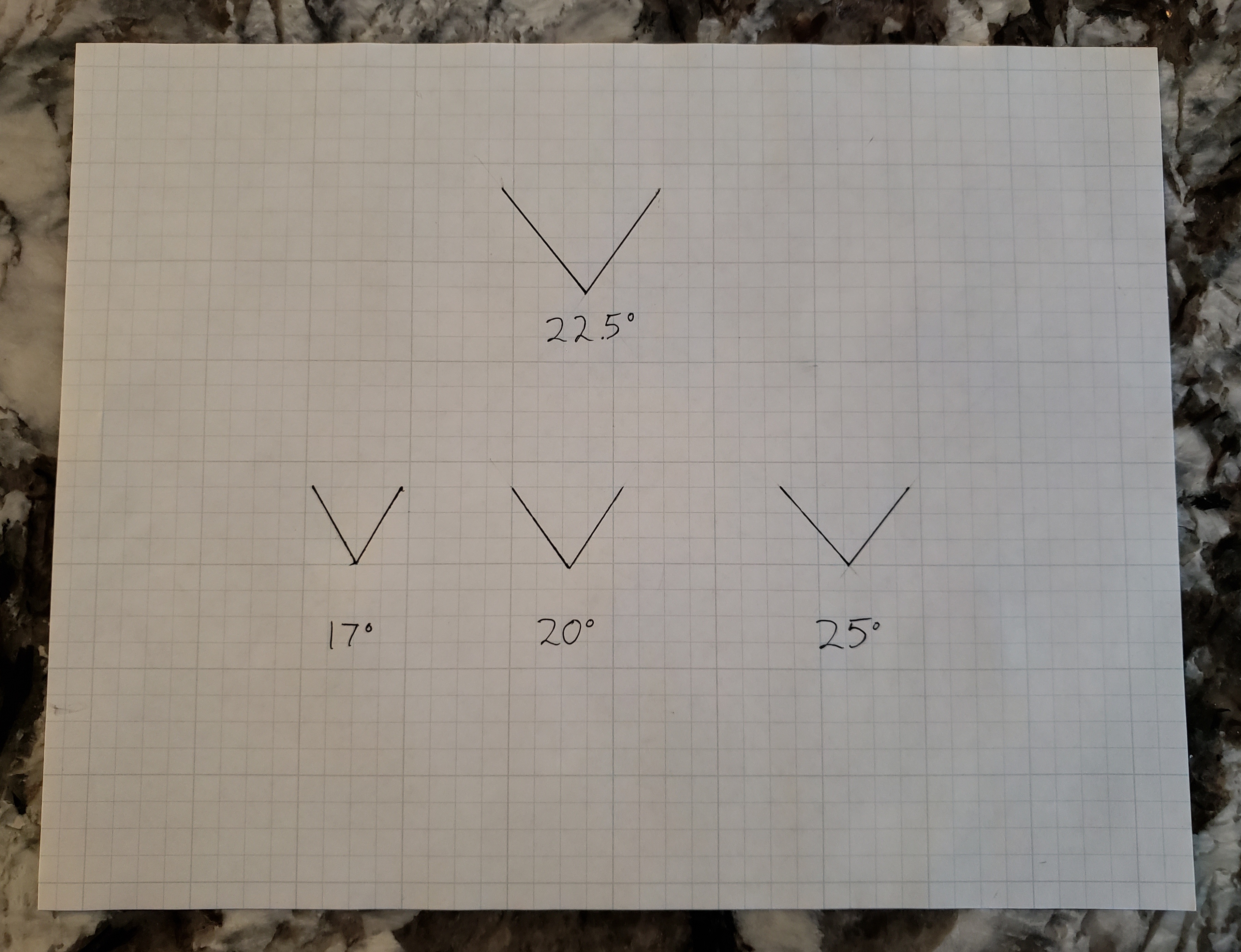

Edges: Angle and Style

The Spine: Jimping, Swedges, and more

The spine of a knife can be customized in several ways as well.

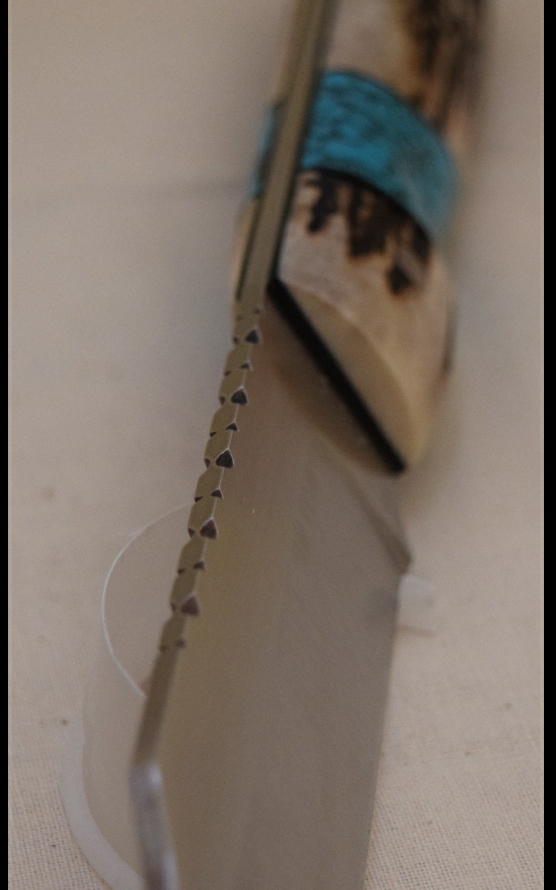

File work on the spine, called “Jimping”, can add a nice touch to a knife. It is often decorative, but can also be functional. When the Jimping is done near the bolster or along the spine of the tang, it can help the user by improving their grip on the knife.

Swedges are secondary bevels on the spine of a knife, most often near the tip of the blade. They are most commonly used on clip point blades but can be found on nearly all different styles of blades. They can be sharpened as well, but are most often not sharpened. When un-sharpened, Swedges are sometimes referred to as “false edges”.

Another factor to consider about the spine of a knife is whether it should be square or rounded. If the knife is going to be used as a survival knife, then the spine being ground to a square 90 deg. angle will allow the user to strike a ferrocerium rod. If this isn’t a concern then the grind of the spine is a purely aesthetic choice, and can be ground however the user prefers.